Transportation Geography, an Observation about Smuggling

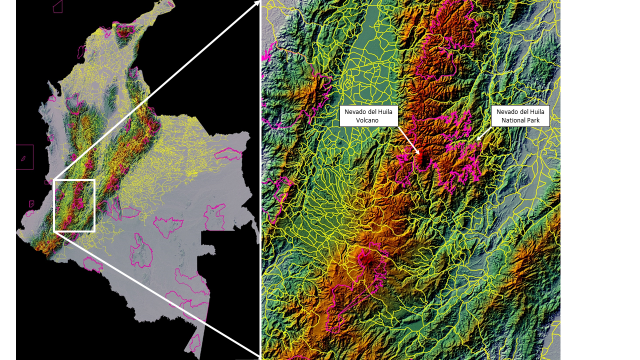

This is a brief research note on geographic theory and practice related to law enforcement and irregular warfare. It uses a piece of cartographic evidence from the Colombian war as an example of how the transportation geography of smuggling differs from that of innocent trade. The difference in the transportation geographies of smugglers as compared to innocent traders is sometimes easy to see on a map. Consider the images below. On the left is an elevation map of Colombia showing the country’s road network in yellow and the national park boundaries in fuchsia. On the right is a blow up of the central cordillera in the southern part of the country. At the approximate center of the image is the Nevado del Huila peak within the national park of the same name.

Road network around the Nevado del Huila volcano.

Colombian scholars and officials describe the high ground of the Nevado del Huila park (where there are no roads shown) as a communications hub. The assertion is obviously true and simultaneously ridiculous. Every map of Colombian road or river networks or of altitudes or seasonal weather disruptions tells the same story, one that every Colombian seems to understand: that there exist regions around which one travels to get places, not through which. The road network in the image, highly developed in the Cauca River valley to the west and in the Magdalena River valley to the east, hardly extends at all into the middle of the central cordillera. The roadless middle is nevertheless a roundhouse for those who wish to elude law enforcement and to have open travel options if they travel under duress. It is indeed a hub for transportation — of contraband and escape. While the contraband areas do not show improved roads that can be used regularly by most motor vehicles, they are typically crisscrossed with trails that can be navigated by foot, pack animal, or perhaps motorcycle. The transportation geography of furtive or fugitive traffic is different from that of innocent traffic. At altitude, the headwaters are easier to cross, ancient pathways lead in all directions, and the urgent traveler can impose intolerable costs and risks on his pursuers. That is to say, the escaper can more easily increase the pursuer’s risks during a pursuit. Any traveler has to be patient in such a region, as passage is not nearly as fast as it would be going around the ‘long’ way. For the innocent traveler, the cost-distances are much greater than they would be using the developed road network. For the smuggler or the guerrilla, however, the extra time pays for the safety of being able to shake off pursuers, the cost of being caught seen as greater than the value of the extra time. In the Nevado del Huila, once a smuggler reaches the remote highlands he can go east to the jungles of Meta and Caquetá, north toward the nation’s capital, west to the Pacific port of Buenaventura, or south, passing out of the Colombian Massif to Ecuador.

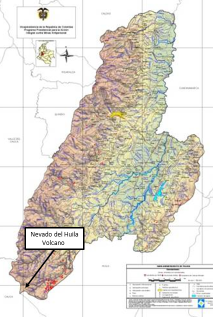

Along with the witness of local authorities, one compelling piece of geographic evidence supporting this assertion regarding the nature of some smuggling transportation hubs is the spatial distribution of landmines in Colombia. The FARC guerrillas especially use landmines during escapes uphill, leaving the cruel devices behind them in order to enhance the effect of the terrain, that is, to impose greater risks on their pursuers. The image below is from a Colombian government agency charged to address the challenge of landmines. It shows Tolima Department, which contains most of Nevado del Huila National Park. Note the landmine concentrations on the slopes leading to the park in southeast Tolima department. Also notice that few landmines are indicated at higher elevations. The pattern repeats itself throughout the country. A reasonable hypothesis holds that that once an escape is successful (in that the pursuers have given up or have been thrown off-track) the fugitives no longer have a need to plant the devices behind them. On the other hand, when a pursuit is successful (those being chased are caught) there is likewise no longer such a need. Not coincidentally, the highland of southern Tolima and northern Cauca departments form the traditional home territory of the FARC.

Landmines in Tolima Department. The bulk of the landmine incidence is displayed in red at the far southeast of the department.

There exist other peculiarities of smuggling geography. A mountain smuggling transportation hub is highlighted here because, although the routes used to transport contraband overlap licit transportation systems, they can be cartographically distinguishable. Perhaps the transportation geography literature will begin to more thoroughly address this phenomenon.